The “native language machine” in our brains

“Native vs. foreign language learning” series: Part 2

Previously, we discussed the overall idea that humans learn “native languages” and “foreign languages” differently.

With this background understanding in mind, we can explore how humans gain grammatical knowledge of their “native languages” in more depth and see why a “native language” is such an important concept to linguists and must be distinctly differentiated from a “foreign language.”

When humans are in their early childhood (and within their critical period of “native language” learning), language input from the external environment is naturally transformed into abstract grammatical knowledge in the brain. For humans without hearing impairments, language input means “speech input”. For those with hearing impairments, language input means “sign input.”

The human brain (within the critical period of native language learning) has a specific area that is wired for the purpose of transforming language input in the environment into abstract grammatical knowledge just through exposure alone.

This brain area allows all of us to gain knowledge of the grammar of our native language completely passively and subconsciously, without any active effort or learning.

The grammatical knowledge of our native language(s) that all of us are hard-wired to gain in early childhood is stored as a sort of implicit grammatical framework in our brains.

Everything that we ever say in our native language is a direct “product” of this implicit grammatical framework.

This means that everything we ever say in our native language, by definition, conforms to the grammatical rules that are in place in the implicit framework--because we would not be able to say that thing in the first place if there were no framework in the brain for us to produce it.

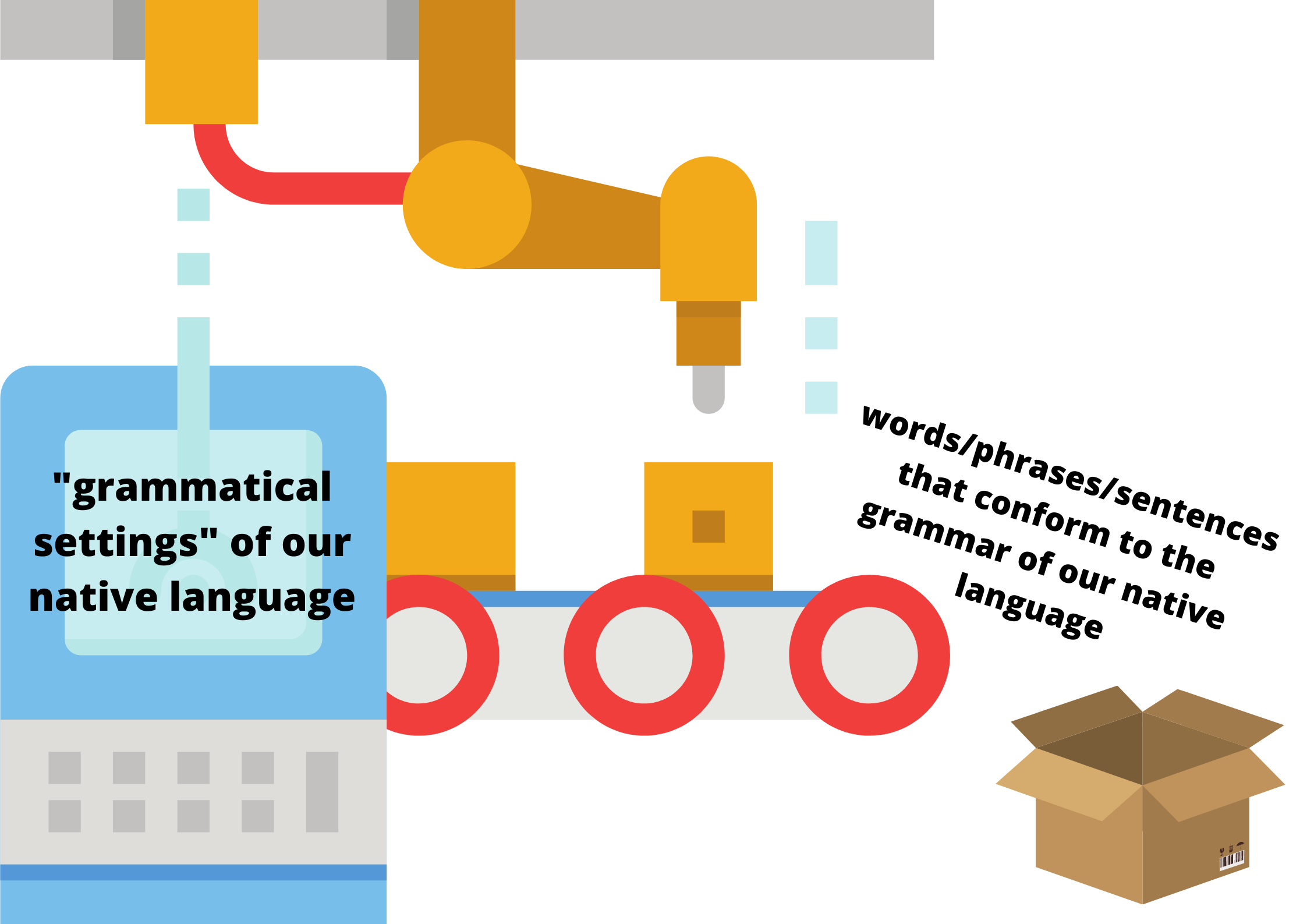

It is useful to use an analogy of a mechanical machine to think about this “native language grammatical framework” in our brains that we are hard-wired to gain in childhood.

Let us imagine that the native language grammatical framework in our brains—which, again, forms naturally during our critical periods—is a mechanical machine that makes red balls.

a “red ball machine”

Inside this machine that makes red balls, there are different components, like red ink and moulds that are shaped like balls.

In other words, “red ink” and “ball-shaped moulds” are the “settings” of this machine.

This machine makes red balls because it has the “settings” of “red ink” and “ball-shaped moulds.” The products of this machine are by definition red balls. This machine would not ever make, say, black cubes, because it has these specific settings.

The implicit grammatical framework in our brains for our native language is like this “red ball machine”--only that, instead of “red ink” and “ball-shaped moulds”, the specific “settings” are the grammatical rules of our native language that we gain naturally in early childhood.

The products of the red ball machine in our analogy will always be red balls moulded by the ball-shaped pressed and sprayed with red ink, because of the machine’s specific settings.

In the same way, the “products” of the implicit native language grammatical framework in our brains will always be words, phrases, and sentences conforming to the grammar of our native language--because the grammatical rules of our native language are the “settings.”

a visualization of the “native language machine” in our brains

When we say something in our native language, the thing we say “comes out” of our “native language machine” conforming to the grammatical “settings” in place. This is just like how red balls come out of the red ball machine as products conforming to that machine’s settings.

The things we say in our native language always reflect the “grammatical settings” in the native language framework that we subconsciously form in early childhood--because the framework is what allows us to say things in the first place!

The order of events is actually like this:

First, we gain the “grammatical settings” of our native language framework passively and naturally through exposure in early childhood.

Then, this “native language machine” allows us to produce everything we ever say in our native language.

Contrary to widespread belief, we do not say things in our native language by consciously applying grammatical rules that we explicitly know.

In fact, it is the exact opposite--we gain a “native language machine” passively in our childhood, and then this “machine” with all the “grammatical settings” of our native language “churns out” all of the things we ever produce in our native language, conforming to these settings.

This is why it is very important to differentiate a “native language” from a “foreign language.”

Humans only learn “native languages” this way--first by passively, subconsciously forming a framework with all the right settings, then producing utterances according to these settings after.

After our critical periods, we are no longer able to form a “native language machine” in our brains. If we want to learn more languages, we can only learn them as “foreign languages”--that means learning explicitly and with conscious effort.

This is also why there is an axiom in Linguistics that “native speakers do not make grammatical mistakes”--even though there is a common misconception that native speakers also make grammatical mistakes.

Just like a red ball machine by definition makes red balls, the native language framework in our brains by definition produces utterances according to the grammar of the language that we are exposed to as children.

So, an opinion like “even native speakers make grammatical mistakes” is as misguided as an opinion like “even a red ball machine makes black cubes.”

Unless a machine “malfunctions,” everything that comes out of it would always be whatever the machine is set up to make.

Our “native language machine” can also “malfunction”--for example, when people suffer brain damage, they can lose the ability to speak their native languages as native speakers.

But without any “malfunction,” our “native language machine” is set up--again, naturally and subconsciously in our early childhood--to produce words, phrases, and sentences according to the grammar of our native language, that is, the language that we are exposed to during our critical periods.

With its specific settings, our “native language machine” literally cannot produce anything other than words, phrases, and sentences that conform to the grammar of that language.

(Note: Other articles will explore the common misconception that “even native speakers make grammatical mistakes.” The ideas of “native speakers” and “native languages” are very important to grasp clearly if we want to learn foreign languages with scientific understanding.)

我們腦中的「母語機器」

「母語學習 vs. 外語學習」系列:第2篇

上一節,我們大致地討論了人類學習「母語」和「外語」的不同。

對這背景有基本理解後,我們可以更深入地探討人類到底如何吸引收「母語」的文法知識,以及了解為何語言學家會如此重視「母語」這概念,並必須把它與「外語」區分開來。

人類在幼兒時期(學習「母語」的關鍵時期),從外在環境中接收到語言訊息(language input),大腦的「語言區域」便會自然地轉化這訊息成這母語的抽象文法知識。對聽力正常的人而言,語言訊息是指在外在環境中的「說話」; 而對於有聽力障礙的人而言,語言訊息則指外在環境中的「手語」。

人類大腦(在學習母語的關鍵時期)有一個特定的區域,專門負責將從外在環境中接收到的語言轉化成抽象的母語文法知識。這區域使我們可以完全被動地,無意識地吸收母語的文法,完全無需主動付出努力去學習。

那些在我們幼兒期就自然獲取的母語文法知識,會形成一個抽象文法框架,儲存於我們的大腦中。

我們用母語說出的一切,都是這套抽象文法框架「製造」出來的「產物」。

這表示我們使用母語所說的話,都必定符合母語框架中的文法規則——因為我們說的任何話,都是要通過這個框架才能說出來的。沒有這框架,我們根本不能說母語。

我們可以用一台實體的機器來比喻這個在我們幼兒時期便自然在腦中形成的母語文法框架。

試想像一下,這套在我們的關鍵時期便成形於腦中的母語文法框架,是一台會製造出一些紅色球體的實體機器。

製造紅球的機器

這機器內部有著不同的組件,例如紅色墨水,以及球狀的模具。

換言之,「紅色墨水」和「球狀模具」就是這台機器的「設置」。

它能製造出紅球,是因為它有「紅色墨水」和「球狀模具」的「設置」。而因為這些特定的設置,它所生產出的會是紅球,而不可能是其他如黑立方之類的產物。

在我們大腦中的母語文法框架就如同這台「紅球製造機」,不過它那特定的設置並非「紅色墨水」和「球狀模具」,而是我們在幼兒時間自然吸收到的「母語文法」。

紅球製造機有著特定的設置,因此它的產物一定是經球狀模具壓制後再噴上紅色墨水的紅球。

同樣,我們大腦中的母語文法框架的「產物」,也總會是符合母語文法的單字、詞組和句子——因為我們的母語文法規則正是那些「設置」 。

我們腦中的「母語機器」的想象圖

當我們說母語時,我們所說的話就是來自那台「母語機器」,所以一定會符合它的文法「設置」,正如從「紅球製造機」生產出的紅球也必定符合機器本身的設置一樣。

我們用母語所說的,都會反映我們在幼兒時期於潛意識中吸收的「母語文法設置」—— 因為這框架就是使我們能運用母語來說話的前提。

換言之,說母語的過程其實是這樣的:

首先,在我們的幼兒時期,單憑從日常環境中接收到語言訊息,便會自然及被動地吸收母語文法,形成腦中母語框架的「文法設置」。

然後,這台「母語機器」會製造出我們使用母語所說的每一句話。

這與普遍人以為的有出入,因為我們其實是不會有意識地運用自己明確知道的文法規則來說母語的。

事實剛好相反——每個人在幼兒時期都會被動地獲得了一台「母語機器」,是這台附帶母語「文法設置」的「機器」讓我們用母語說話的,而因為這「機器」是「產出」母語的,我們所有用母語說的話都是符合它的「文法設置」的。

這就是為甚麼把「母語」和「外語」區分開來是如此重要。

人類是被動地、無意識地在腦中形成一個包含所有母語文法設置的框架,然後通過這些設置生成母語的話語——這是只有吸收和說「母語」時才會發生的。

在關鍵時期結束後,我們的大腦便再無法形成「母語機器」。如果我們想學習其他的語言,就只能把它們當作「外語」來學習——即明確地、有意識地學習。

這也是為何語言學中有一道「母語人士不會犯文法錯誤」的公認原則——儘管普遍人仍然對此有誤解,以為母語人士也會犯文法錯誤。

正如「紅球製造機」只會生產紅球一樣,在我們大腦中的母語框架也只會根據母語的文法來產出母語的話語。

因此,那些「即使母語人士也會犯文法錯誤」的想法是錯誤的,這就好像在說「即使紅球製造機也會生產出黑立方」一樣。

除非機器出現故障,否則它製造出的始終會是按設置而造成的產物。

當然,我們的「母語機器」也可能會出現「故障」——例如當人們腦部受傷時,便可能會失去說母語的能力。

但只要沒有任何「故障」,這台在我們幼兒時期便自然形成的「母語機器」,必定會根據母語的文法去產出單字、詞組和句子。

因為其特定的設置,我們的「母語機器」實際上無法輸出除了符合母語文法的單字、詞組和句子以外的產物。

(備註:其他文章將討論到「即使母語人士也會犯文法錯誤」這常見誤解。如果我們真的想以科學性的角度來學習外語, 釐清「母語人士」和「母語」這兩個概念是十分重要的。)